ENGINE ROOM

The Travis AFB Aviation Museum features twenty-one major displays and several smaller exhibits in its Engine Room. These span the evolution of aircraft propulsion, from piston engines to turboprops, turbojets, turbofans, and even rocket engines. Three cutaway displays allow visitors to see the inner workings of these powerful machines. Stop by the Engine Room and discover what keeps aircraft moving.

PISTON ENGINES

A piston engine, also known as a reciprocating engine, burns fuel inside enclosed cylinders. The resulting combustion forces pistons to move up and down within the cylinders. These pistons are connected to a crankshaft, which converts this motion into rotation to turn the propeller.

Piston engines can be built in several cylinder arrangements. For larger aircraft, manufacturers found the radial engine to be especially effective. In this design, the cylinders are arranged in a circle around the propeller shaft, providing efficient cooling, reliability, and strong power output.

LIBERTY L-12

The Liberty L-12 was a water-cooled, V-12 aircraft engine producing 440 horsepower. In 1917, a federal task force challenged the nation’s top engine designers to create a powerful aircraft engine as quickly as possible. The requirements were ambitious: a high power-to-weight ratio and a design suitable for mass production. In just five days, the team completed the basic design.

By July 1917, an eight-cylinder prototype was sent to Washington for testing. A twelve-cylinder version followed in

August and was quickly approved. The War Department then placed an order for 22,500 engines, dividing production among major engine and automobile manufacturers, including Buick, Ford, Cadillac, Lincoln, Marmon, and Packard.

Although Cadillac was initially selected to produce Liberty engines, General Motors founder William Durant opposed using company facilities for wartime production due to his pacifist beliefs. As a result, Cadillac president Henry Leland resigned and founded the Lincoln Motor Company specifically to manufacture Liberty engines. Lincoln built a new factory in record time and produced 2,000 engines within its first 12 months. Durant later reversed his position, and both Cadillac and Buick ultimately joined Liberty engine production.

The Liberty engine proved highly adaptable, powering not only aircraft but also a variety of tanks. By the time of the Armistice in November 1918, manufacturers had produced 13,574 Liberty engines, reaching a peak production rate of 150 engines per day. Production continued after the war, with a total of 20,478 engines built between 1917 and 1919.

WRIGHT CYCLONE R-1820

The Wright Cyclone R-1820 was a nine-cylinder, single-row, air-cooled radial aircraft engine. Depending on the model and configuration, it produced between 700 and 1,500 horsepower. Production began in 1931 and continued well into the 1950s, making it one of the most widely used American aircraft engines of its era.

In addition to Wright Aeronautical, the R-1820 was built under license by several manufacturers, including Studebaker, Lycoming, and Pratt & Whitney. The engine was also produced internationally as the Soviet M-25 and the Spanish Hispano-Suiza 9V.

The R-1820 represented the continued development of the earlier Wright P-2 engine first introduced in 1925. One of its key improvements was increased displacement, which resulted in

significantly greater horsepower. The design proved highly successful and powered a wide range of aircraft, including the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, Grumman J2F Duck, Curtiss P-36, Boeing 307 Stratoliner, and Douglas SBD Dauntless.

Beyond aviation, modified versions of the Cyclone were adapted for ground use. A gasoline-powered variant was developed for the American M6 heavy tank, while a diesel version was used in the M4A6 Sherman tank.

WRIGHT R-2600 TWIN CYCLONE

In 1935, Curtiss-Wright began development of a more powerful successor to its successful R-1820 Cyclone. The result was the R-2600 Twin Cyclone, a 14-cylinder, two-row, air-cooled radial engine. Producing up to 1,600 horsepower, the R-2600-3 was originally intended to power the Curtiss C-46 Commando. However, changing operational requirements led to the selection of the larger Pratt & Whitney R-2800 instead.

Despite this, the R-2600 became one of the most important American aircraft engines of World War II. It powered several key production aircraft, including the Douglas A-20 Havoc, North American B-25 Mitchell—famously used by Lt. Col. Jimmy Doolittle during the first bombing raid on Tokyo—the Grumman TBF Avenger, Curtiss SB2C Helldiver, and the PBM Mariner flying boat.

More than 50,000 R-2600 engines were produced during the war at Curtiss-Wright plants in Caldwell, New Jersey, and Cincinnati, Ohio.

PRATT & WHITNEY R-2800 DOUBLE WASP

The Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp was the first 18-cylinder radial aircraft engine developed in the United States. After its initial test run in 1937, it quickly distinguished itself as one of the smallest and most compact engines in its class. That compact design, however, created early challenges—particularly in dissipating heat from the tightly packed cylinder heads—which had to be overcome before the engine could enter operational service.

By 1939, the R-2800 was introduced into service producing 2,000 horsepower, an astonishing output for an air-cooled

engine of the era. Contemporary liquid-cooled engines could barely match its performance. In October 1940, a U.S. Navy Vought F4U Corsair powered by an R-2800 set a world speed record of 403 mph in level flight.

The Double Wasp went on to power many of the most famous fighters and medium bombers of World War II. Aircraft such as the Republic P-47 Thunderbolt, Northrop P-61 Black Widow, Douglas A-26 Invader, Vought F4U Corsair, and Grumman F6F Hellcat all relied on the R-2800’s power and reliability. Experimental aircraft like the XP-56 Black Bullet also utilized the engine. By the end of the war, improved versions of the Double Wasp were producing up to 2,800 horsepower with remarkable reliability.

After World War II, the R-2800 continued to serve in civilian aviation, powering aircraft such as the Convair 440, Douglas DC-6, Martin 404, and early models of the Lockheed Constellation.

Between 1939 and 1960, a total of 125,334 R-2800 engines were produced. More than seventy years after its introduction, the venerable Double Wasp remains in service today, still powering restored vintage aircraft around the world.

LYCOMING G-50-O480-B1B6

The Lycoming O-480 was a high-performance, air-cooled, six-cylinder, horizontally opposed aircraft engine. It powered a wide range of general aviation aircraft, including the Aero Commander, Beech Twin Bonanza and Queen Air, and the Helio Courier. A geared and supercharged variant of the O-480 was used in military and utility aircraft such as the L-23B/D Beech Seminole, Beech Twin Bonanza F-50, Dornier Do 27-H2, and Aeritalia AM-3C, where improved high-altitude and short-field performance were required.

Lycoming’s history dates back to 1907, when its parent compa-

ny was reorganized as the Lycoming Foundry and Machine Company, initially producing automobile engines and later becoming a subsidiary of the Auburn Automobile Company. Although Lycoming’s early aircraft engines were primarily radial designs, the company entered the light-aircraft engine market in 1938 with the introduction of the O-145, an air-cooled, four-cylinder, horizontally opposed engine. This design philosophy would become the foundation of Lycoming’s long-standing dominance in general aviation propulsion.

WRIGHT R-3350 DUPLEX-CYCLONE

The Wright R-3350 Duplex-Cyclone was a twin-row, supercharged, air-cooled radial engine with 18 cylinders. Depending on the model, power output ranged from 2,200 to more than 3,700 horsepower. Along with the Pratt & Whitney R-4360 Wasp Major, it was among the most powerful radial aircraft engines produced in the United States.

Although the R-3350 prototype first ran in May 1937, the engine was slow to mature. Its complexity posed significant engineering challenges, and Wright initially focused much of its effort on the smaller R-2600. As war clouds gathered in Europe, the U.S. Army Air Corps issued a requirement for a long-range bomber capable of carrying a 2,000-pound bomb load from the United States to Germany should Britain fall to Nazi Germany.

Three of the four bomber proposals submitted in response to this requirement were designed around the R-3350, prompting an accelerated development program so the engine could be brought into production. In 1941, the R-3350 began flight testing when it replaced the Allison V-3420 on the Douglas XB-19 prototype.

The Boeing B-29 Superfortress was ultimately selected as the new long-range bomber. When paired with the R-3350, however, deficiencies in airflow to the rear row of cylinders led to chronic overheating and engine fires—problems that plagued the B-29 throughout World War II.

After the war, the R-3350 was extensively redesigned,

R-3350

Cutaway of R-3350

eliminating many of the issues that had affected it during wartime service. In its refined form, the engine became a favorite for large postwar aircraft, most notably the Lockheed Super Constellation and the Douglas DC-7.

PRATT & WHITNEY R-4360 MAJOR WASP

The Pratt & Whitney R-4360 “Major Wasp” was a 28-cylinder, four-row, air-cooled radial engine and represented the pinnacle of American radial-engine development. Each row of seven cylinders was slightly offset from the previous one, creating a semi-helical arrangement that improved airflow to the rear rows. This distinctive configuration gave rise to the engine’s well-known “corncob” nickname.

The R-4360 was the most technically advanced and mechanically complex reciprocating aircraft engine produced in the United States. Depending on the variant, it generated

between 3,000 and 4,300 horsepower, making it the most powerful production piston aircraft engine ever to enter service.

Designed primarily for heavy bombers and long-range transports, the Major Wasp powered aircraft such as the Boeing C-97 Stratofreighter, C-124 Globemaster II, Boeing B-50 Superfortress, Convair B-36 Peacemaker, and the Northrop B-35 Flying Wing. The engine also found limited use in high-performance fighters, most notably the Goodyear F2G Corsair and the Republic XP-72.

Between 1944 and 1955, Pratt & Whitney produced seven major variants of the R-4360, with total production reaching 18,697 engines. Though ultimately eclipsed by jet propulsion, the Major Wasp remains a landmark achievement in piston-engine aviation history.

TURBOPROP

A turboprop is an engine that uses a turbine, similar to a jet engine, to turn an aircraft propeller. Air is drawn into the intake, compressed, and mixed with fuel in the combustion chamber. The resulting hot gases spin the turbine, which powers both the propeller and the compressor. Most of the thrust comes from the propeller, with the exhaust contributing only a small amount.

PRATT & WHITNEY T34 TURBP WASP

A turboprop uses a jet turbine to drive the propellers. In 1945, the U.S. Navy contracted Pratt & Whitney to develop a turboprop engine. Although the Navy funded the research and tested the engine on two Navy Lockheed R7V-2 Constellation (C-121) variants, it was the U.S. Air Force that ultimately adopted the T34 and put it into production, not the Navy.

In September 1950, a modified Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress served as a test bed for a T34 turboprop mounted in the nose. The first operational application of the T34 was the Boeing YC-97J Stratofreighter, which later evolved into the Aero Spacelines Super Guppy.

A key difference between a piston engine and the T34 turboprop is the RPM operating range. A turbine engine operates efficiently only within a relatively narrow range of high RPM, while a piston engine can function effectively over a much broader RPM range. This affects propeller operation: the turbine engine requires less RPM change for a given power increase, providing a more rapid response. Consequently, the propeller’s pitch change mechanism must operate much faster than it would with a piston engine.

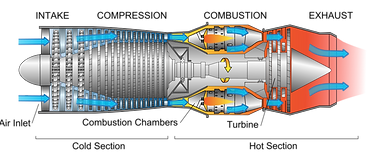

TURBOJET

A turbojet is the simplest form of gas turbine aircraft engine and produces essentially all of its thrust from the high-velocity exhaust gases leaving the engine. Air is drawn into the intake, compressed, mixed with fuel, and ignited in the combustion chamber. The expanding hot gases pass through the turbine—

driving the compressor—and then exit through the exhaust nozzle to generate thrust. In a pure turbojet, all of the intake air passes through the entire engine core, unlike turbofans, which divert some air around the core.

Turbojets are most efficient at high speeds and high altitudes, but they are noisy and relatively fuel-inefficient at lower speeds, which led to their replacement by turbofan engines in most modern aircraft.

GENERAL ELECTRIC J31 TURBOJET

In 1940, inventor Sir Henry Tizard led a British delegation to the United States to discuss the exchange of critical technological secrets in return for American industrial support in the war against Germany. Among the most important technologies shared was Frank Whittle’s pioneering W.1 turbojet engine.

The Whittle W.1 served as the foundation for General Electric’s I-A, America’s first operational jet engine. This design was further developed into the I-16, which the U.S. Army Air Forces later designated as the J31. The J31 became the first jet engine to be mass-produced in the United States, marking a turning point in American aviation history.

In 1941, at the urging of General Henry “Hap” Arnold, the J31 was selected to power America’s first jet-powered aircraft, the Bell P-59 Airacomet. General Electric and Bell Aircraft Corporation jointly produced 66 P-59s. Although none of these aircraft saw combat, the program provided invaluable experience in jet propulsion and high-speed flight. The P-59 achieved a noteworthy service ceiling of approximately 46,700 feet.

Producing 1,650 pounds of thrust and weighing about 850 pounds, the J31 earned its reputation as the godfather of American jet engine technology. General Electric ultimately built 241 J31 engines, concluding the program in 1945, having laid the groundwork for every U.S. turbojet that followed.

GENERAL ELECTRIC J33 TURBOJET

The J33-A-37 turbojet engine was developed by General Electric in response to a 1943 U.S. Army request for a 3,000–4,000-pound-thrust jet engine. Its design evolved directly from GE’s wartime work with Frank Whittle’s W.1 engine, which had been shared with the United States during the Second World War.

To meet wartime production demands, manufacture of the J33 was licensed to the Allison Division of General Motors. The engine on display here is the very first J33 assembled by Allison. Following the end of the war, the Army reevaluated its jet engine program and transferred all J33 production entirely to Allison.

The J33 employed a single-stage, double-entry centrifugal-flow compressor feeding fourteen straight-through combustion chambers. A single-stage axial-flow turbine, located behind the combustion chamber assembly, drove the compressor. In this configuration, nearly three-quarters of the power produced was consumed by the compressor, leaving only about one-quarter available to produce thrust. This inherent limitation of early centrifugal-flow designs resulted in a thrust output of 3,900 pounds for an engine weighing 1,820 pounds.

The J33 holds several important distinctions: it was GE’s first turbojet of its own design, its last all-centrifugal-flow turbojet, and the final centrifugal-flow engine used in U.S. military combat aircraft.

The J33 powered many first-generation American jet aircraft, including the Martin XB-51, Lockheed XP-81, F-80A/B/C Shooting Star and its numerous trainer and reconnaissance variants (T-33 series), North American F-86C, Northrop F-89J Scorpion, Bell XP-83, and several experimental and prototype designs.

WESTINGHOUSE J34 TURBOJET

The Westinghouse J34 (company designation Westinghouse 24C) was a turbojet engine developed by the Westinghouse Aviation Gas Turbine Division in the late 1940s. Essentially an enlarged version of the earlier J30, the J34 produced 3,000 pounds of thrust, roughly double that of its predecessor. Later variants equipped with an afterburner produced up to 4,900 pounds of thrust. The J34 first flew in 1947.

Developed during a period of extremely rapid advancement in gas-turbine technology, the J34 was largely obsolete by the time it entered service and frequently served as an interim

powerplant. One notable example was the Douglas X-3 Stiletto, which was fitted with two J34 engines after the intended Westinghouse J46 proved unsuitable.

The X-3 was designed to investigate sustained supersonic flight. However, the substitution of the J34 left the aircraft severely underpowered, and it was unable to exceed Mach 1 in level flight.

Produced during the transition from piston-engined aircraft to jets, the J34 was also used as an auxiliary engine on aircraft such as the Lockheed P-2 Neptune and the Douglas D-558-2 Skyrocket. In addition, it powered several experimental aircraft, including the McDonnell XF-85 Goblin parasite fighter and the Lockheed XF-90, a prototype intended as a long-range interceptor.

GENERAL ELECTRIC J47 TURBOJET

The General Electric (GE) J47 turbojet, developed from the earlier GE J35, made its first flight in 1948. Following this successful debut, demand for the engine increased rapidly. GE’s Lynn, Massachusetts facility soon proved incapable of meeting the military’s growing requirements, prompting the company to seek an additional production site.

GE ultimately selected a location near Cincinnati, Ohio, formally opening the new plant on February 28, 1949. This facility—later known as Evendale—initially complemented J47 production at Lynn and would eventually become GE Aviation’s world

headquarters. During the Korean War, the exceptionally high demand for the J47 made it the most widely produced gas turbine engine in the world. It powered nearly all new U.S. front-line jet aircraft of the era, including the famed MiG-killing North American F-86 Sabre.

The J47 achieved several important milestones in aviation history. It became the first turbojet engine certified for civil use by the U.S. Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA) and was among the earliest engines to employ an afterburner system to significantly increase thrust.

By the end of the 1950s, more than 35,000 J47 engines had been produced, making it the most mass-produced turbojet in history. The engine remained in military service until 1978. The J47 powered a wide variety of aircraft, including the North American B-45 Tornado bomber, Consolidated-Vultee B-36 bomber (as auxiliary boost engines), Boeing B-47 Stratojet bomber, Martin XB-51 attack bomber, North American F-86 Sabre fighter, North American FJ-2 Fury fighter, Republic XF-91 interceptor, Chase XC-123A transport, and Boeing KC-97 Stratotanker (boost power).

This specific engine, a J47-GE-17, powered the North American F-86D Sabre and the Italian-built Fiat F-86K interceptor.

PRATT & WHITNEY J57

The Pratt & Whitney J57 was the company’s first internally designed turbojet and represented a major technological breakthrough. It featured a twin-spool axial-flow compressor, a substantial departure from earlier centrifugal-flow engines. The J57 was an immediate success, with its performance widely described in superlative terms. By adopting the axial-flow configuration, Pratt & Whitney effectively leapfrogged the industry with its very first turbojet design. In recognition of this achievement, the J57 was awarded the prestigious Collier Trophy in 1952 for the greatest achievement in American aviation.

In 1953, a J57 powering the North American F-100 Super Sabre became the first production aircraft to exceed the speed of sound in level flight, a feat accomplished on its maiden flight. Other aircraft powered by the J57 included the Convair F-102 Delta Dart, the Chance Vought F8U-1 Crusader—which set an official speed record in excess of 1,000 mph—the Lockheed U-2 high-altitude reconnaissance aircraft, the Republic F-105 Thunderchief prototype, and Northrop’s SM-62 Snark intercontinental guided missile.

The commercial derivative of the J57, designated the JT3, was so far ahead of its competition that nearly every major U.S. aircraft manufacturer designed an airliner around it. In 1958, four JT3 engines powered Pan American World Airways’ Boeing 707 on its inaugural jet service from New York to Paris. The 707 cruised at 575 mph, approximately 225 mph faster than the fastest propeller-driven airliners of the era.

When production of the J57 and JT3 concluded in 1965, a total of 21,186 engines had been built for military and commercial applications.

PRATT & WHITNEY J-60-P-6 TURBOJET

Pratt & Whitney Canada began the design of the Pratt & Whitney J60 turbojet—known in civilian service as the JT12—in July 1957. Responsibility for the program was transferred to Pratt & Whitney Aircraft in the United States in January 1958. One of Pratt & Whitney’s final turbojet designs, the JT12 produced 3,300 pounds of thrust and was the smallest turbojet ever built by the company.

The engine first ran on May 16, 1958, and made its first flight in January 1960 aboard a Canadair CL-41 Tutor. Deliveries of production engines began in October 1960. Production

continued until 1977, by which time 2,269 JT12/J60 turbojet engines had been built, along with 352 JFTD12 turboshaft derivatives (military designation T73).

The single-spool JT12/J60 powered several notable light jet aircraft, including the North American Sabreliner (military designation T-39) and the Lockheed JetStar (military designation C-140). Military applications included the Fairchild SD-5 surveillance drone and the North American T-2B Buckeye, the U.S. Navy’s first production jet trainer. The specific engine variant shown here, the J60-P-6, powered the T-2B.

A turboshaft variant of the engine, designated JFTD12 (T73), was developed for rotary-wing applications and powered the Sikorsky S-64 Skycrane heavy-lift helicopter, known in U.S. military service as the CH-54 Tarhe.

PRATT & WHITNEY J52‑P‑3 TURBOJET

Although the Hound Dog’s engine is not typically displayed, it serves as a representative example of a classic 1950s turbojet engine.

The North American Aviation AGM‑28 Hound Dog was a supersonic, turbojet‑powered, nuclear‑armed air‑launched cruise missile, developed in 1959 for the United States Air Force. Its primary mission was to destroy Soviet ground‑based air defense sites ahead of a bomber strike, allowing B‑52 Stratofortress aircraft to penetrate hostile airspace during the Cold War.

Originally designated B‑77, the missile was later redesignated GAM‑77, and finally AGM‑28. The Hound Dog was conceived as an interim standoff weapon for the B‑52 until the introduction of the GAM‑87 Skybolt air‑launched ballistic missile. When Skybolt was canceled, the Hound Dog remained in service far longer than intended, serving for approximately 15 years before being replaced by more advanced systems such as the AGM‑69 SRAM and later the AGM‑86 ALCM.

Power was provided by a Pratt & Whitney J52‑P‑3 turbojet, housed in a pod mounted beneath the rear fuselage of the mis-

sile. While the J52 engine family was widely used in aircraft such as the A‑4 Skyhawk and A‑6 Intruder, the J52‑P‑3 variant was specifically optimized for missile use. Unlike aircraft installations that required long service life and throttle variability, the Hound Dog’s engine was designed to operate at maximum power for the duration of the mission.

As a result of this high‑stress operating profile, the missile version of the J52 had an extremely limited operational life of approximately six hours. This was considered acceptable, as the Hound Dog was expected to complete its mission and self‑destruct well within that time frame.

TURBOFAN

A turbofan engine uses a large fan at the front of the engine to move a significant mass of air. Some of this air passes through the engine core, where it is compressed, mixed with fuel, and burned, while the remainder bypasses the core and flows around it. The bypassed air produces thrust directly and mixes with the core exhaust to increase overall efficiency. In a high-bypass turbofan, the majority of the air bypasses the core, providing most of the engine’s thrust while reducing fuel consumption and noise compared to turbojets.

PRATT & WHITNEY TF30 TURBOFAN

The Pratt & Whitney (P&W) TF30 was a military low-bypass turbofan engine originally designed for the subsonic F6D Missileer aircraft. Although the Missileer program was canceled, the TF30 was later adapted with an afterburner for supersonic applications. In this configuration, it became the world’s first production afterburning turbofan engine. The TF30 went on to power the General Dynamics F-111 and the early F-14A Tomcat, and it was also used—without an afterburner—in early versions of the Vought A-7 Corsair II. The TF30 first flew in 1964, and production continued until 1986.

The General Dynamics F-111 experienced significant inlet compatibility problems with the TF30. Many of these issues were attributed to the placement of the engine intakes behind disturbed airflow from the wing, which adversely affected engine performance. Later F-111 variants incorporated improved intake designs, and most were equipped with more powerful versions of the TF30.

The Vought A-7A used a non-afterburning version of the TF30, as close air support missions did not require supersonic performance. TF30 engines were retained on the A-7B and A-7C models as well.

Early F-14 Tomcats were also powered by the TF30, but the engine proved to be underpowered for the aircraft. More critically, the TF30 was ill-suited to the demands of air combat and was prone to compressor stalls at high angles of attack, particularly if the throttles were moved aggressively. These shortcomings ultimately led to the replacement of the TF30 with the General Electric F110-GE-400 engines in later F-14 variants.

GENERAL ELECTRIC TF39 TURBOFAN

In 1965, the U.S. Air Force contracted General Electric (GE) to develop an engine for the next generation of strategic cargo aircraft, the Lockheed C-5A Galaxy. In response, GE introduced the TF39, the world’s first high-bypass turbofan engine. With substantially increased takeoff thrust and reduced fuel consumption, the TF39 was the most advanced engine of its class.

Equipped with state-of-the-art turbine cooling technology and a uniquely designed thrust reverser, the TF39 featured an 8-to-1 bypass ratio, a 25-to-1 compressor pressure ratio, and an as-

tounding turbine inlet temperature of approximately 2,500°F. Between 1968 and 1971, a total of 463 TF39-1 and -1A engines were produced and delivered to power the initial C-5A fleet.

More than a decade later, Lockheed—under contract to the U.S. Air Force—developed 50 improved C-5B aircraft and subcontracted GE to deliver 200 TF39-1C engines and thrust reversers. The first TF39-1C rolled off the assembly line in January 1985, and by November 1988 the final engine had been delivered.

GE would ultimately carry forward the TF39 legacy with the development of the CF6 engine family, which went on to power aircraft such as the McDonnell Douglas DC-10, Boeing 747, and MD-11. The TF39 and CF6 lineage also led to the creation of the LM2500 gas turbine, which remains in service today powering naval and commercial ships in the United States and around the world.

SOVIET MIKULIN AM-5/ TUMANSKY RD-9

The Tumansky RD-9, initially designated the Mikulin AM-5, was an early Soviet turbojet engine developed independently and not derived from German or British designs. The AM-5 became available in 1952 and completed state testing in 1953, producing approximately 5,700 pounds of thrust without afterburner. The engine was significant in that it enabled the first Soviet supersonic interceptor, the MiG-19, as well as the first Soviet all-weather area interceptor, the Yak-25. Following Sergei Tumansky’s replacement of Alexander Mikulin as chief designer of OKB-24 in 1956, the engine was redesignated RD-9.

ROCKET ENGINES

Rocket engines are fundamentally different from air-breathing engines such as turbojets and turbofans. They are reaction engines, operating on Newton’s third law of motion: for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. A rocket produ-

ces thrust by expelling mass at high velocity in one direction, generating an opposing force that propels the vehicle forward.

In a rocket engine, fuel and an oxidizer—a substance that provides oxygen—are carried onboard and injected into a combustion chamber. When ignited, this mixture burns rapidly, producing extremely hot, high-pressure gases. These gases are then expanded and accelerated through a shaped nozzle, converting thermal energy into kinetic energy and producing thrust.

Because rockets carry their own oxidizer, they can operate in the vacuum of space as well as within an atmosphere, unlike conventional aircraft engines that rely on ambient air for combustion.

AEROJET GENERAL XLR73

The Aerojet General XLR73 was a proposed rocket engine for the X-15 program. It featured a single thrust chamber using white fuming nitric acid (WFNA) as the oxidizer and jet fuel as the propellant. The engine initially produced 10,000 lbf at sea level, but the introduction of an improved nozzle increased thrust to 11,750 lbf. A key advantage of the XLR73 was that it was restartable in flight and continuously throttleable between 50 and 100 percent thrust, both critical requirements for a piloted hypersonic research aircraft.

Early engine studies for the X-15 considered several candidates, including the Bell XLR81, Aerojet General XLR73, North American NA-5400, and Reaction Motors XLR10. As the program matured, engineers increasingly favored the Reaction Motors approach. This led first to the XLR30, a scaled-up derivative of the XLR10 concept, and ultimately to the XLR99, which became the definitive X-15 powerplant.

The XLR99’s adoption reflected lessons learned from the earlier candidates: the need for high thrust, deep throttling, in-flight restart capability, and operational reliability for a manned aircraft operating across a wide flight envelope.

AEROJET LR87-AJ-11 ROCKET ENGINE

The Aerojet LR87-AJ-11 was an American liquid-propellant rocket engine used on the first stage of the Titan II intercontinental ballistic missile and associated launch vehicles. Although it consisted of two separate combustion chambers, each with its own turbopump machinery, the LR87 was designed, tested, and flown only as a single integrated engine unit and was never intended to operate as a single-chamber engine.

The LR87 first flew in 1959 and was developed in the late 1950s by Aerojet. In the AJ-11 configuration used on Titan II,

the engine produced approximately 430,000 lbf (1.9 MN) of thrust at sea level, increasing to about 470,000 lbf in vacuum.

The LR87 was notable as the first production rocket engine family capable of operating on all three major liquid-propellant combinations, depending on variant:

-

RP-1 and liquid oxygen

-

Liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen (proposed/experimental variants)

-

Hypergolic propellants (Aerozine 50 and nitrogen tetroxide)

The engine operated on an open gas-generator cycle and employed regeneratively cooled combustion chambers. Each thrust chamber assembly used a single high-speed turbine that drove lower-speed centrifugal fuel and oxidizer pumps through reduction gearing. This arrangement improved turbopump efficiency, reduced propellant consumption in the gas generator, and increased overall specific impulse.

The LR87 design served as the direct template for the Aerojet LR91, which powered the second stage of the Titan missile family.

The LR87 was a fixed-thrust engine and could not be throttled or restarted in flight. Early versions used on Titan I burned RP-1 and liquid oxygen. Because liquid oxygen is cryogenic and cannot be stored for long periods, it had to be loaded shortly before launch.

For Titan II, the LR87-AJ-11 was redesigned to burn Aerozine 50 and nitrogen tetroxide, which are hypergolic and storable at room temperature. This conversion allowed Titan II missiles to remain fully fueled and ready for rapid launch, a critical requirement for nuclear deterrence.

AEROJET LR91-AJ-11 ROCKET ENGINE

The Aerojet LR91 was an American liquid-propellant rocket engine used on the second stages of Titan intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and later Titan launch vehicles. The LR91-AJ-11 produced approximately 105,000 pounds of thrust in vacuum.

Early LR91 engines, flown on the Titan I, burned RP-1 (kerosene) and liquid oxygen (LOX). Because liquid oxygen is cryogenic, it could not be stored in the missile for extended periods and had to be loaded shortly before launch, limiting operational readiness.

For the Titan II, the LR91 was modified to use Aerozine-50 fuel and nitrogen tetroxide (N₂O₄) oxidizer. These propellants are hypergolic, meaning they ignite spontaneously upon contact, and are storable at room temperature. This change allowed Titan II missiles to remain fully fueled and ready to launch on short notice, a critical requirement for a strategic missile system.

The LR91-AJ-11 operated on a gas-generator cycle, in which a small portion of propellant was burned to power the turbopumps. The thrust chamber was regeneratively cooled using fuel flowing through cooling passages, while the nozzle extension employed a separate ablative skirt to withstand prolonged high-temperature operation.

Vacuum Optimization

The LR91 was a vacuum-optimized engine, designed to operate most efficiently at high altitude. A rocket nozzle achieves maximum efficiency when exhaust pressure at the nozzle exit closely matches the surrounding ambient pressure.

At sea level, ambient pressure is high, so first-stage engines use shorter, less-expanded nozzles to prevent exhaust flow separation. In a vacuum, ambient pressure is extremely low, allowing exhaust gases to expand much more. If a sea-level nozzle were used in vacuum, the exhaust plume would continue expanding beyond the nozzle walls, reducing efficiency.

To address this, vacuum-optimized engines such as the LR91 use larger expansion ratios, resulting in longer and wider nozzles that allow the exhaust to expand fully, maximizing thrust and efficiency in near-vacuum conditions.